Around The World, Part 2: Plate tectonics

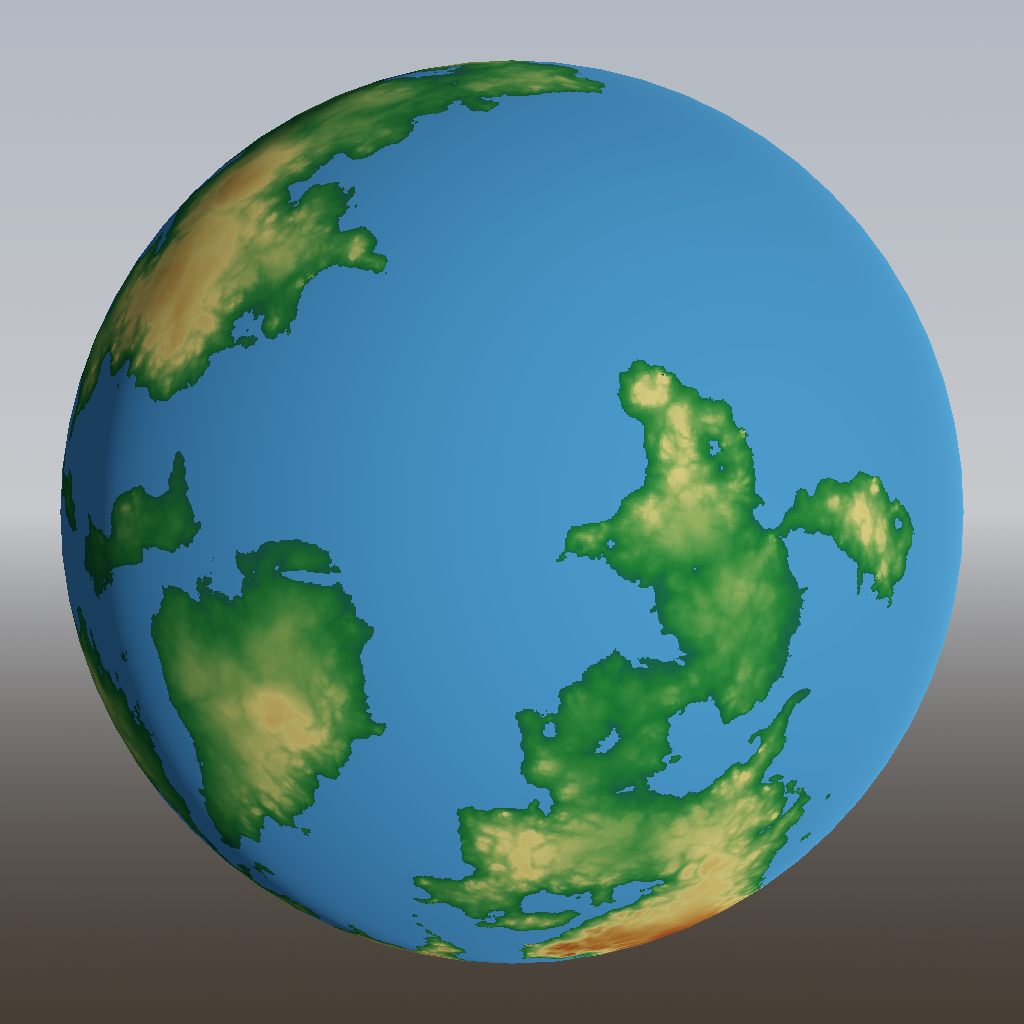

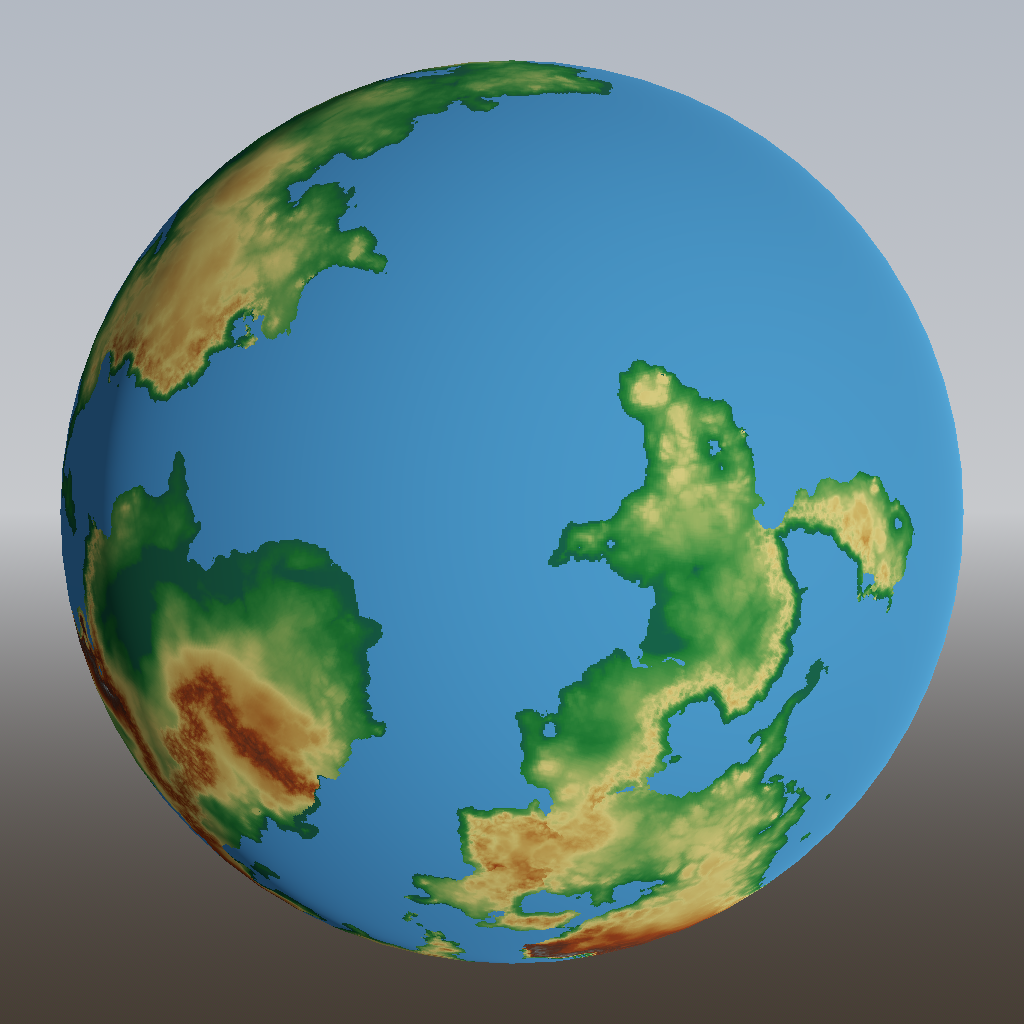

In the previous post, we tackled generation of continent shapes using Voronoi cells and set some base heights using curves and simplex noise:

Last time, I already alluded to plate tectonics and how they affect geography. Let’s look at that in a bit more detail.

Too much on my plate

The Earth is covered by crust, which is the solid rock upon which we live. The crust floats upon the mantle, which is also made of rock, but so hot that it’s liquid. Parts of crust freely float around on the mantle. Such a connected piece of crust is called a tectonic plate, or plate for short. Over billions of years, plates shift around, merge and break up again.

There are two types of crust: continental and oceanic. Continental crust is thicker and lighter, causing it to float higher on the mantle and being pushed above water level; oceanic crust is thinner and denser, causing it to lie lower on the mantle and form the ocean floor.

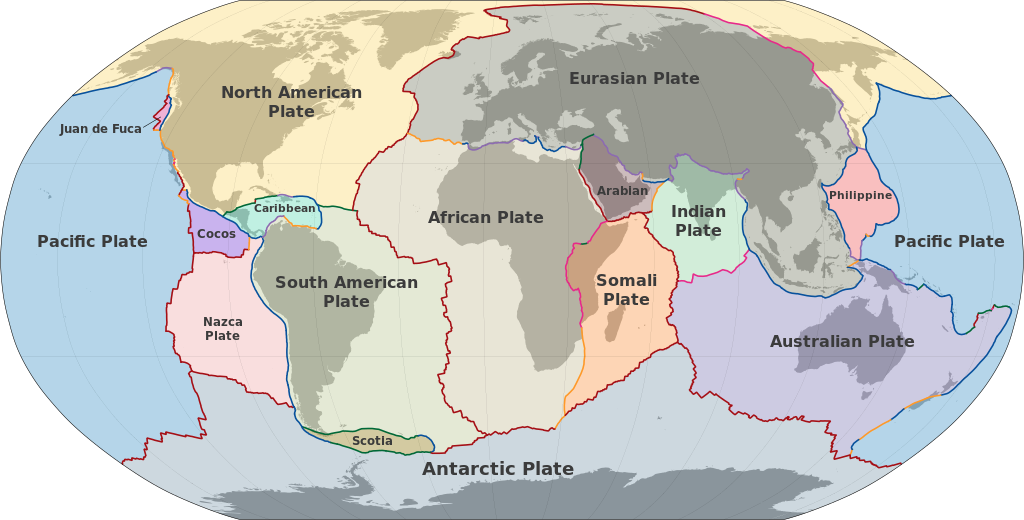

Some procedural generation algorithms and blogs will tell you that there are continental and oceanic plates, but this is not true; Most plates contain both continental and oceanic crust, as you can see from this picture on Wikipedia:

Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC-SA 3.0

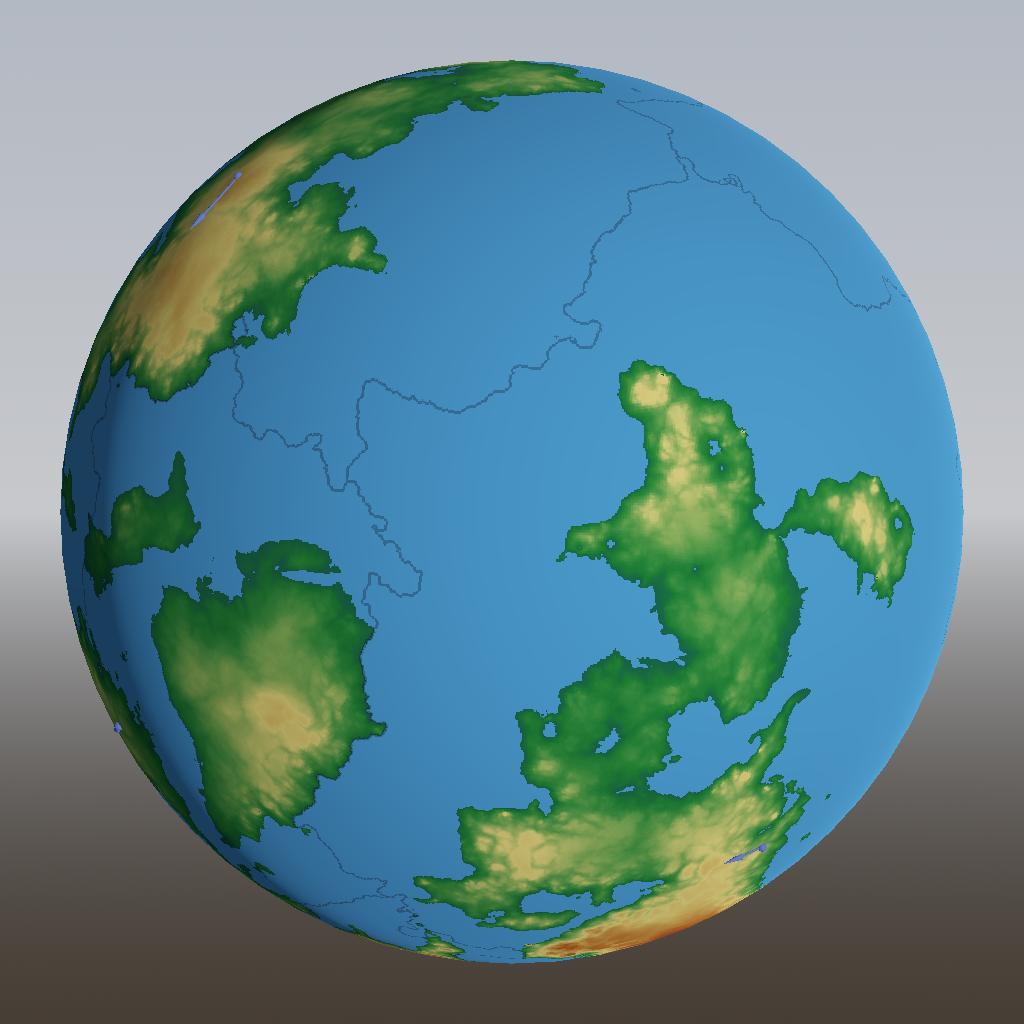

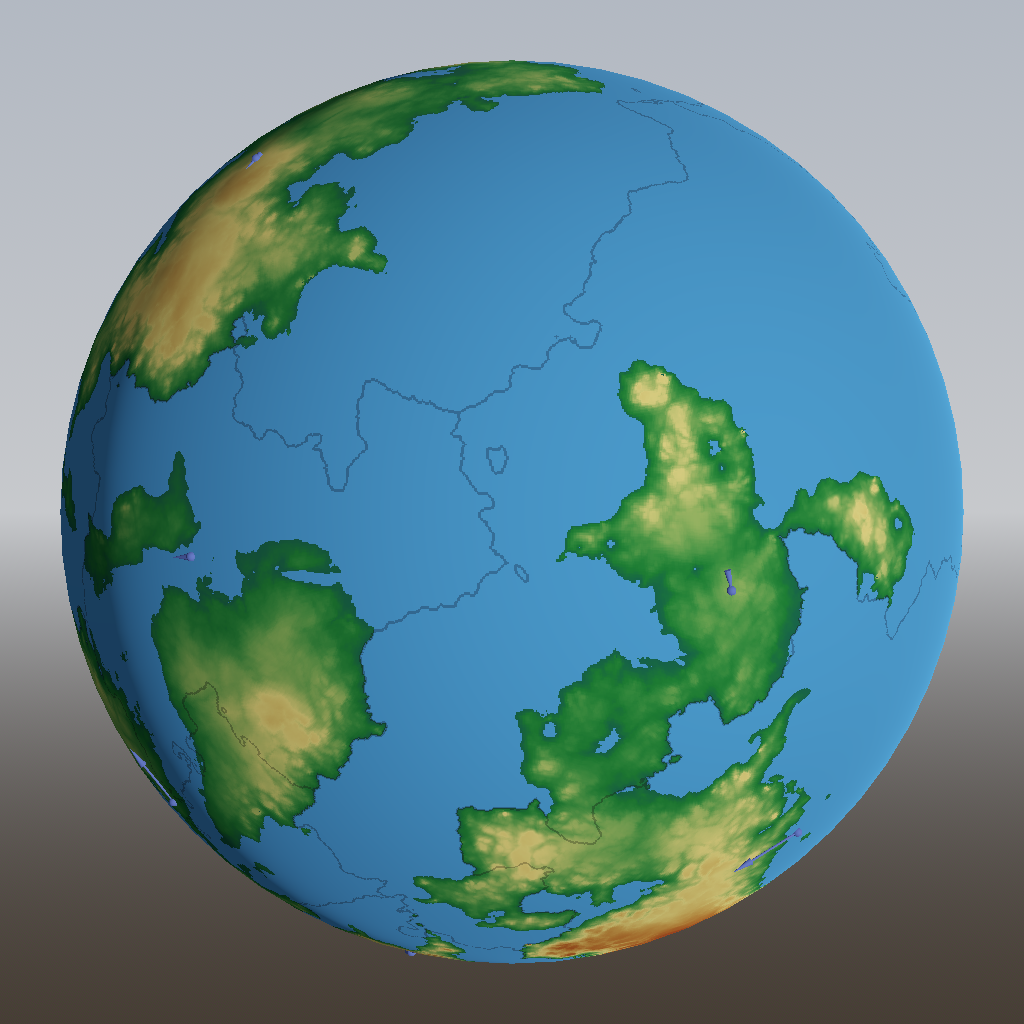

Let’s try to simulate that effect in our world too. First, notice that continents are mostly contained within one plate, so let’s start with plates consisting of just our continental Voronoi regions. Then, we simultaneously grow each plate outwards, connecting Voronoi regions to that plate as we go:

As you can see, this causes some nice fracture lines in between the continents. Not too bad, but looking at the Earth map again, we see that some plates have oceanic crust on only one side. We can do that too: instead of growing uniformly outwards, each continent receives a preferred direction in which it will grow more quickly.

It doesn’t make a big difference in this example, but we’ll keep it.

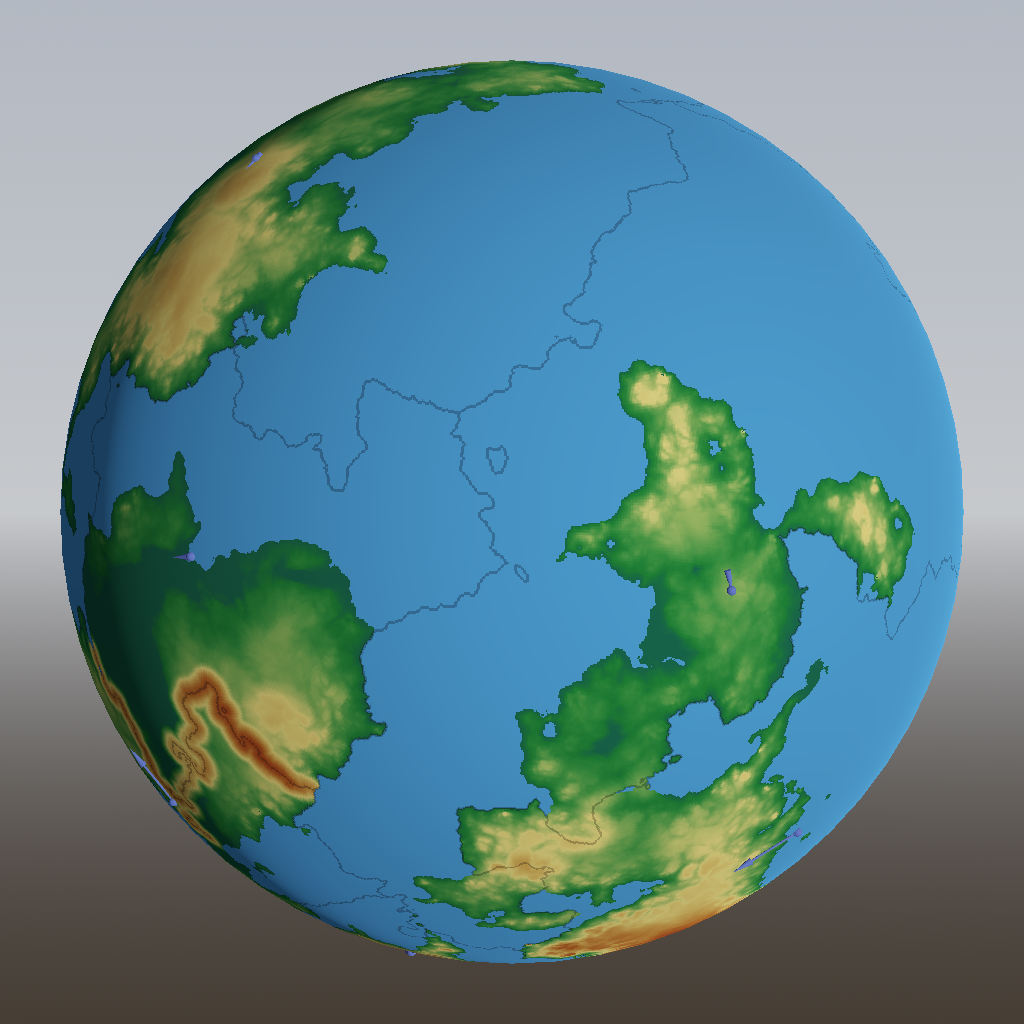

The other thing you might notice about the Earth map is that there are more plates than continents. There are 6 continents, but about 15 plates. So let’s randomly break plates up in two:

You can see that the two continents at the bottom now each span two plates.

With each plate, I’m also calculating the plate’s velocity. This is drawn as a blueish arrow; they’re a bit hard to see but you can find one at the bottom left.

How exactly plates are set in motion is still a bit of a mystery. Part of it is probably that they’re pulled along by flows of molten rock in the mantle. Part of it also seems to be interactions at plate boundaries: plates sliding underneath other plates tend to be pulled under, and new oceanic crust being formed at mid-ocean ridges tends to push those plates apart. It’s that latter effect that I implemented here. It doesn’t matter much; the important thing is that we assign some speed and direction to each plate, so that we can properly implement…

Plate interactions

What happens along the boundary between to plates depends on the type of crust (continental or oceanic) and whether the plates are moving towards each other (converging) or away from each other (diverging). Let’s start with the most interesting case: two pieces of continental crust colliding with each other. This is what’s currently (very slowly) happening between the Indian plate and the Eurasian plate, and it causes both plates to crumple up and form a mountain range, the Himalayas.

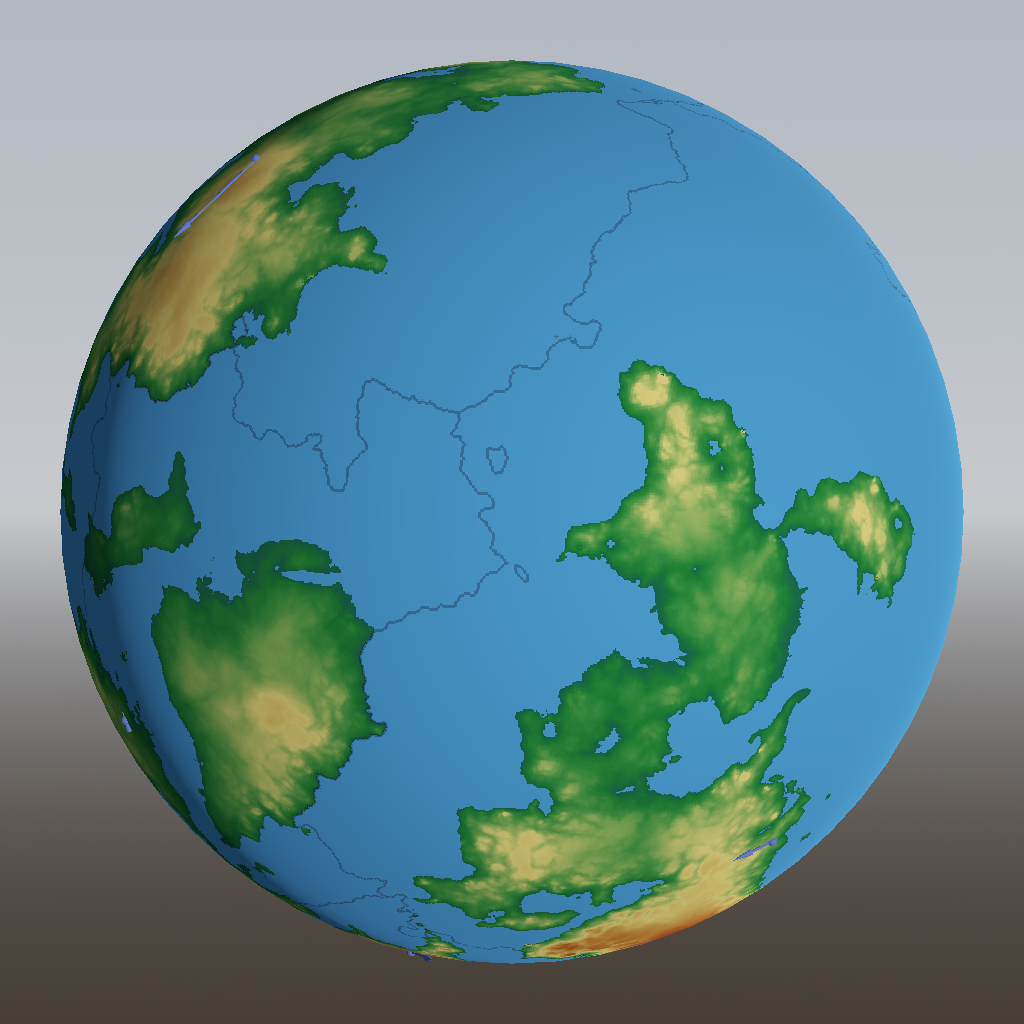

To add mountain ranges in our world, we can detect where two pieces of continental crust are on a collision course, and add a mountain-shaped curve to the height there:

You see we’ve created quite a nice mountain range in the bottom left continent, because those plates are colliding at a relatively large speed. However, the mountain range looks a bit too smooth. And the solution to that is always: more simplex noise! Here, I added noise to both the distance (width) of the mountain range, as well as the height:

That makes those mountains a lot more interesting and realistic.

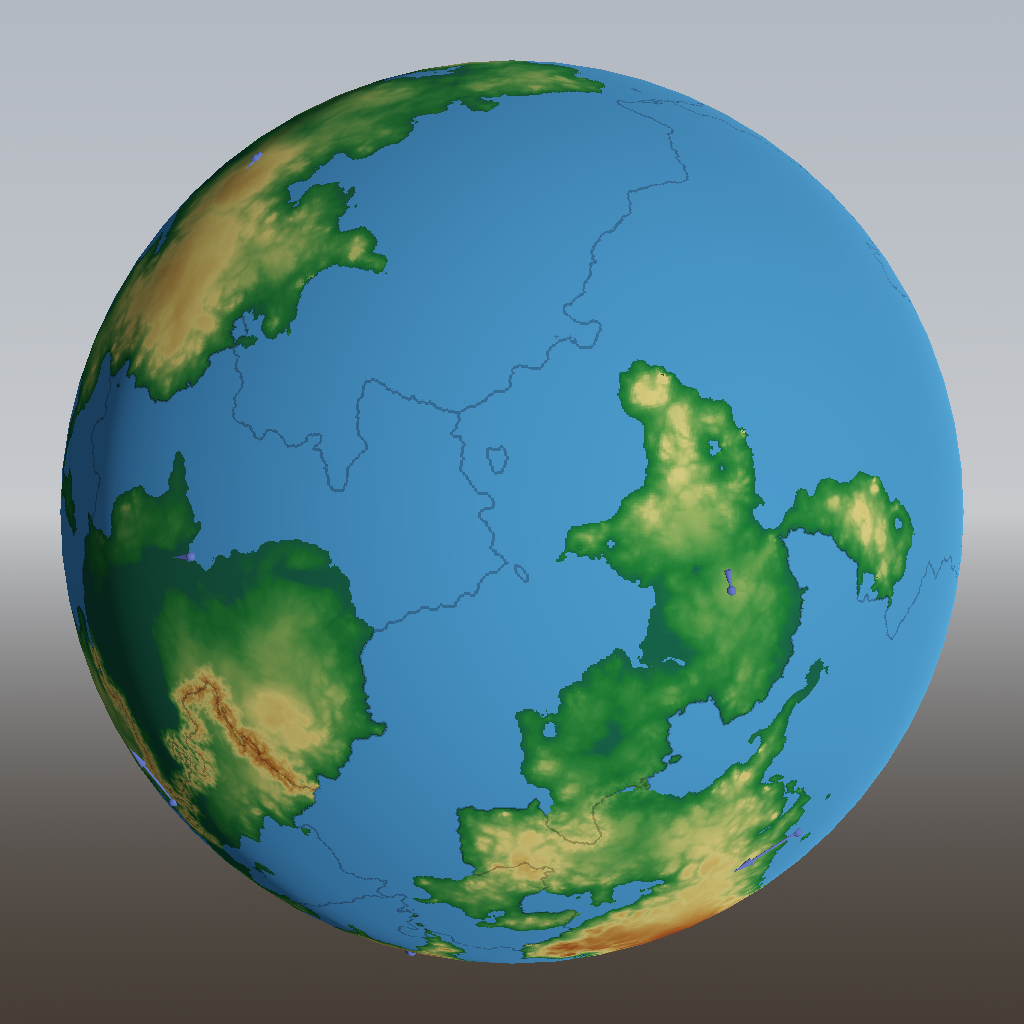

Now that we have the code to apply a curve with noise, we can use it to produce other effects at tectonic boundaries:

- Continental/continental convergent boundaries can not only produce mountains, but also plateaus, where one plate is being pushed up by the other sliding underneath it.

- Continental/continental divergent boundaries produce rift valleys, which make the land around the boundary lower.

- Oceanic/oceanic divergent boundaries produce mid-oceanic ridges, because lava flows out of the gap between the plates, and stacks up to form a volcanic ridge.

- Oceanic/oceanic convergent boundaries produce island arcs, as one plate subducts beneath the other, and the other is pushed upwards above sea level.

- Continental/oceanic divergent boundaries produce… I don’t know, actually. Probably some sort of ridge on the oceanic side.

- Continental/ocanic convergent boundaries cause the oceanic crust to subduct beneath the continental crust. This causes a deep trench on the oceanic side, and an arc of volcanoes on the continental side.

With all that added, our world looks like this:

You can spot the plateau behind the mountain range in the bottom left, and a volcanic arc alongside the right side of the bottom right continent.

(Geologists might notice that I’m not covering a third direction of motion, the transform boundary, where plates slide along each other without converging or diverging. The reason I’m omitting them is that pure sliding never happens: if you look closely enough, it’s always sections of the boundary either converging or diverging, and handled accordingly.)

This is almost enough to create a plausible height map for our game. However, there are some more finishing touches to be done, which will be the subject of the next post.