Around The World, Part 1: Continents

There’s this game concept that has been on my mind for years, and I can’t seem to let it go. You step into the wet, salt-crusted shoes of the naval explorers of old: Columbus, Da Gama, Magellan, Cook. Most of the world is still a big unknown question mark: here be dragons. There are no satellites, no GPS, not even maps. The only way to find out what’s out there is to actually go there – which is a risky venture. Your navigational tools: a compass, the sun, moon and stars, and any information you might learn from the locals along the way. Your goal: to find a route around the world and end up where you started.

The prototype

When the 10th Alakajam! game jam came around with the triple theme of “Ships, Maps and Chaos”, I knew I had to build a prototype of this game. That became Around The World, and it worked. The combination of map reading, trading, and managing the risk of going out there with limited supplies turned out to be interesting.

So a few months ago, I started work on a bigger game based on this concept. I’m still tentatively calling it Around The World, but the name may change before release. I can’t promise that I’ll have time to blog about it every step of the way, but I’ll try.

Procedural generation

The real Earth has been fully mapped and explored, so that would make for a boring game. I could create a different world by hand, but then the player would know it after a few playthroughs, which is bad for replayability. So I’m turning to the indie game developer’s best friend: procedural generation. Every playthrough, the world will be created from scratch by a series of algorithms.

In the first instalment of this blog series, we’re going to set the stage, and develop an algorithm that creates some continents for us.

A sphere is the most perfect shape

The prototype took place on a rectangular map, with the left side wrapping around to the right to form a cylinder. Polar ice caps prevented you from going off the top or bottom. Many games do this and get away with it, but because I’m a perfectionist, I want my game to take place on an actual sphere.

This should give interesting gameplay decisions: you can stay near the equator, which is the long route, but relatively safe and you can benefit from trade winds – or you go around a pole, which is shorter, but has more averse weather and icebergs to deal with.

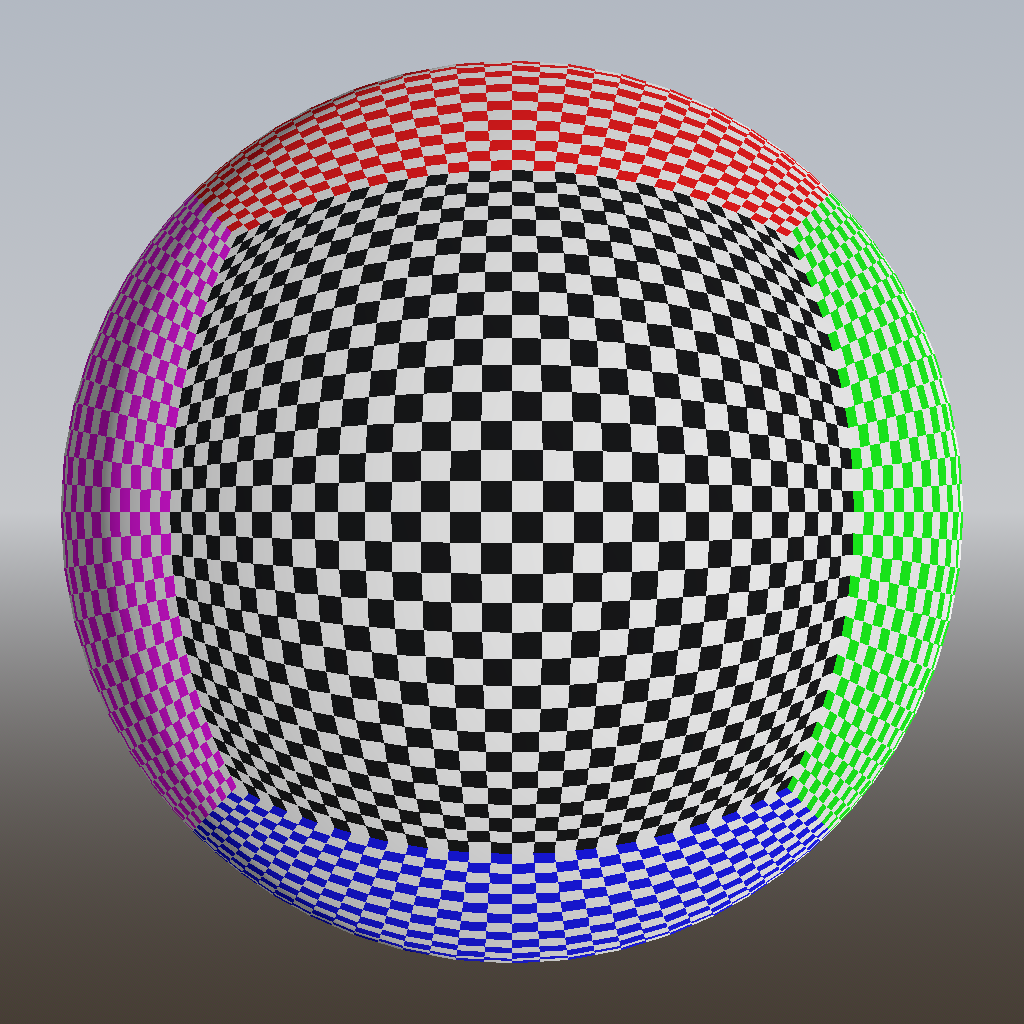

The real world has infinite resolution, but we’re working in a finite computer, so we have to reduce our world to some kind of grid. Unfortunately, there’s no way to divide a sphere up into a grid of equal-sized shapes, like squares, triangles or hexagons. It’s just mathematically impossible. In the end, I chose to use a quadrilateralized spherical cube instead: six square grids in the shape of a cube, which is then projected onto the sphere:

However, there is a problem with this mapping. As you can see, the squares near the corners are quite a bit smaller than the central ones, and much distorted from their true square shape. This means that we can’t simply assume that each square is the same size, which will complicate our algorithms.

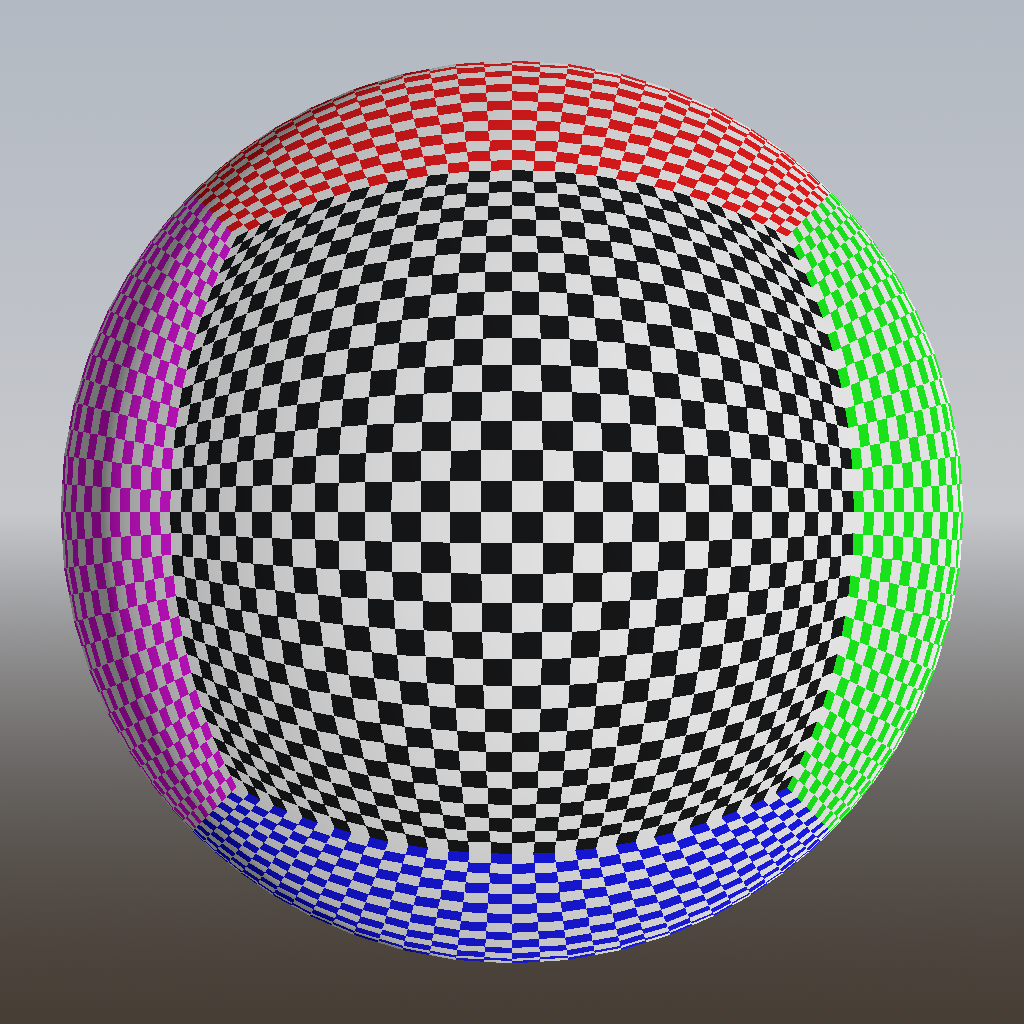

To mitigate this a bit, we can borrow a trick from Google’s S2 library: apply a nonlinear transformation to the coordinates on the cube, before projecting them onto the sphere. The result is not perfect (it can’t be), but quite a bit better (less bulging):

The exact transformation used by S2 is not documented, but we can find it by reading the source code. I’m using their tangent projection, which is the best but also the slowest. Without the transformation, corner squares are 5.2 times smaller in area than center squares. With the projection, they are only 1.414 times smaller, which is a small enough difference that we can (and will) ignore it in most cases. Because the projection is a bit slow, I calculate it only once for each cell and store the results in a cache.

Fake it till you make it

On Earth, our landmasses are made up of tectonic plates, which float around on a layer of molten rock called the mantle. These plate tectonics are the main driver for large-scale geographical features: continents, islands, mountains, trenches, volcanoes and so on. So it’s useful to have a basic understanding of how this stuff works.

In the past, I have experimented with actually simulating plate tectonics. It was cool to see all the continents drifting around on the sphere, but I realized it was useless for this game: it gave me, as a game designer, very little control over how the world turned out. To make the game playable, I might need to set limits such as: have six continents, not too big or too small, and evenly distributed across the globe. A physical simulation makes it very hard to do that, so I decided to fake it.

Continent shapes

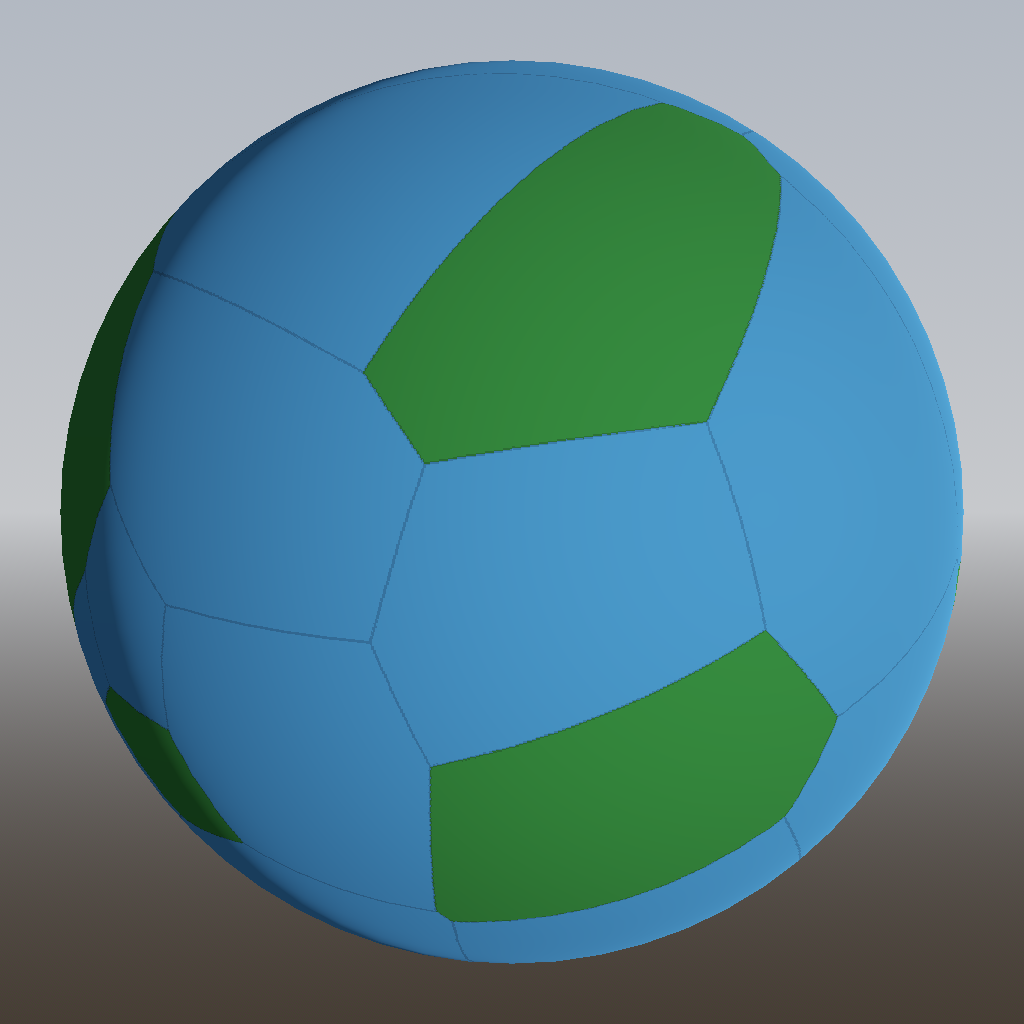

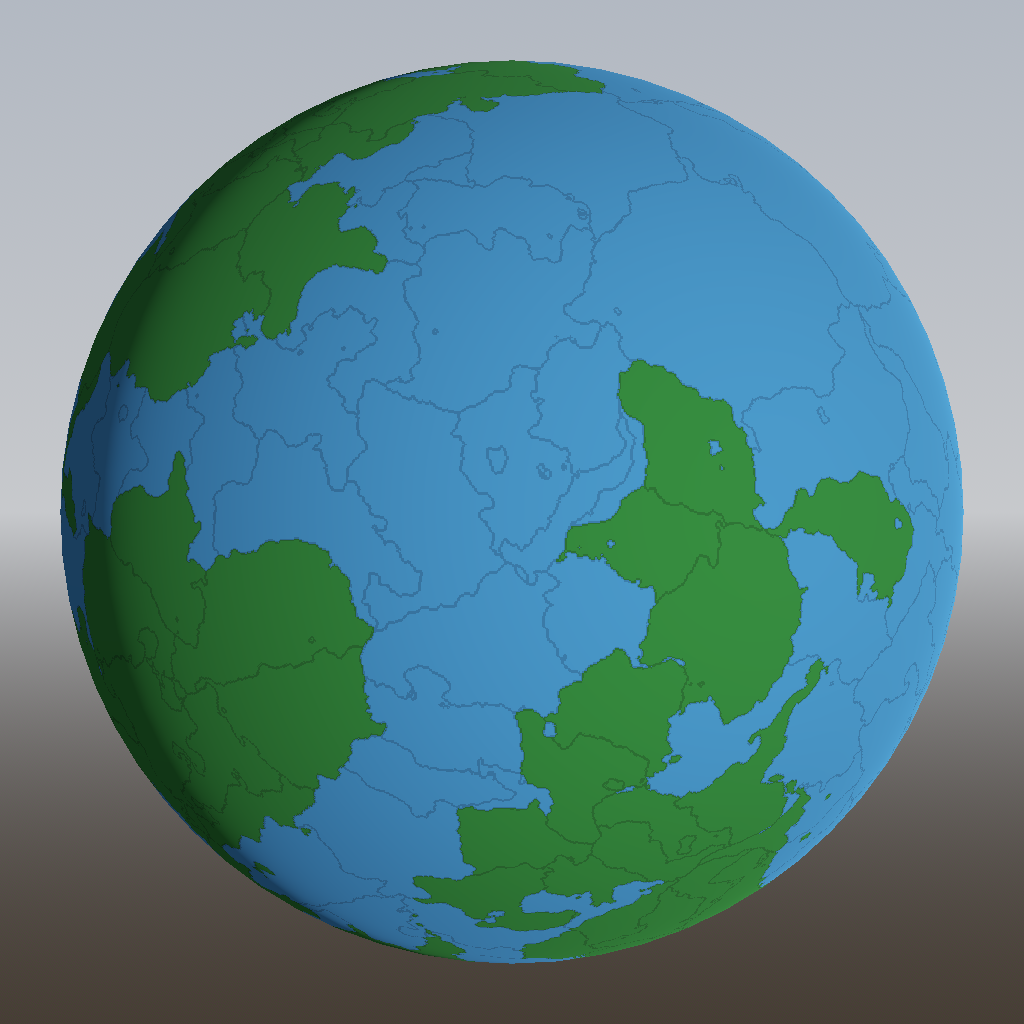

A common way to create random-looking shapes is the Voronoi diagram. Simply generate some random points, called seeds, and assign each other point to the seed that’s closest to it. Afterwards, we decide for each seed whether this will be land or water. Here’s how that looks on our sphere:

Earth has six continents, covering about 29% of its surface. To match that ratio, I generated 21 Voronoi regions and randomly designated 6 of them to be land (green).

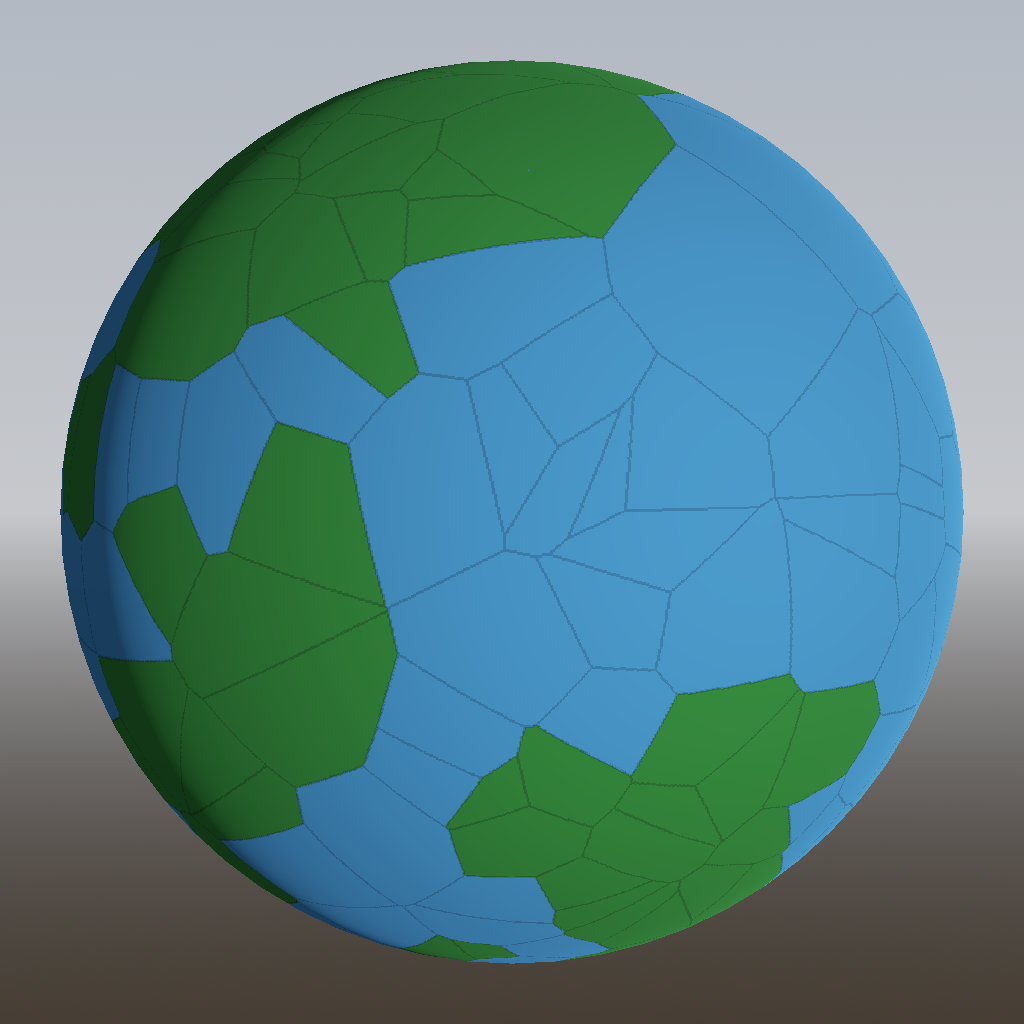

It’s a start, but we can do better. The problem with Voronoi regions is that they are always convex, so there can never be any indents in the continent shapes. Boring! So what we can do is create more, smaller Voronoi regions, and assign multiple regions to the same continent. We start each continent from a single region, then randomly grow it by including neighboring regions, until we have enough land. Here’s the result:

Much better! Those are starting to look like plausible shapes for our landmasses.

But they’re still rather straight and boring. To fix that, we can use another trick from the procedural generation book: domain warping. For each point, instead of immediately looking for its closest Voronoi seed, we first jiggle the point a bit. Points near these straight boundaries might then get jiggled across the boundary, and end up being assigned to another Voronoi region.

Let’s introduce yet another common procgen building block: simplex noise. I won’t explain what simplex noise is here; in case you don’t know, just think of it as a magic machine that you can put coordinates of a point into, and it spits out a random value between -1 and 1. If you put the same point into it again, you get the same value out; and if your point is slightly different, you’ll get a slightly different output value.

To do this “jiggling” of points then, we can create three instances of simplex noise, one for each of the x, y and z components. To each point we add a small amount of this noise before assigning it to its closest Voronoi region. This has the effect of breaking up the straight lines:

Those would be some great continent shapes to explore! Note that the domain warp sometimes causes bits of Voronoi regions to form an “enclave” inside another region. These are actually inland oceans (very deep), but they look like lakes, so I didn’t bother removing them.

Scaling the heights

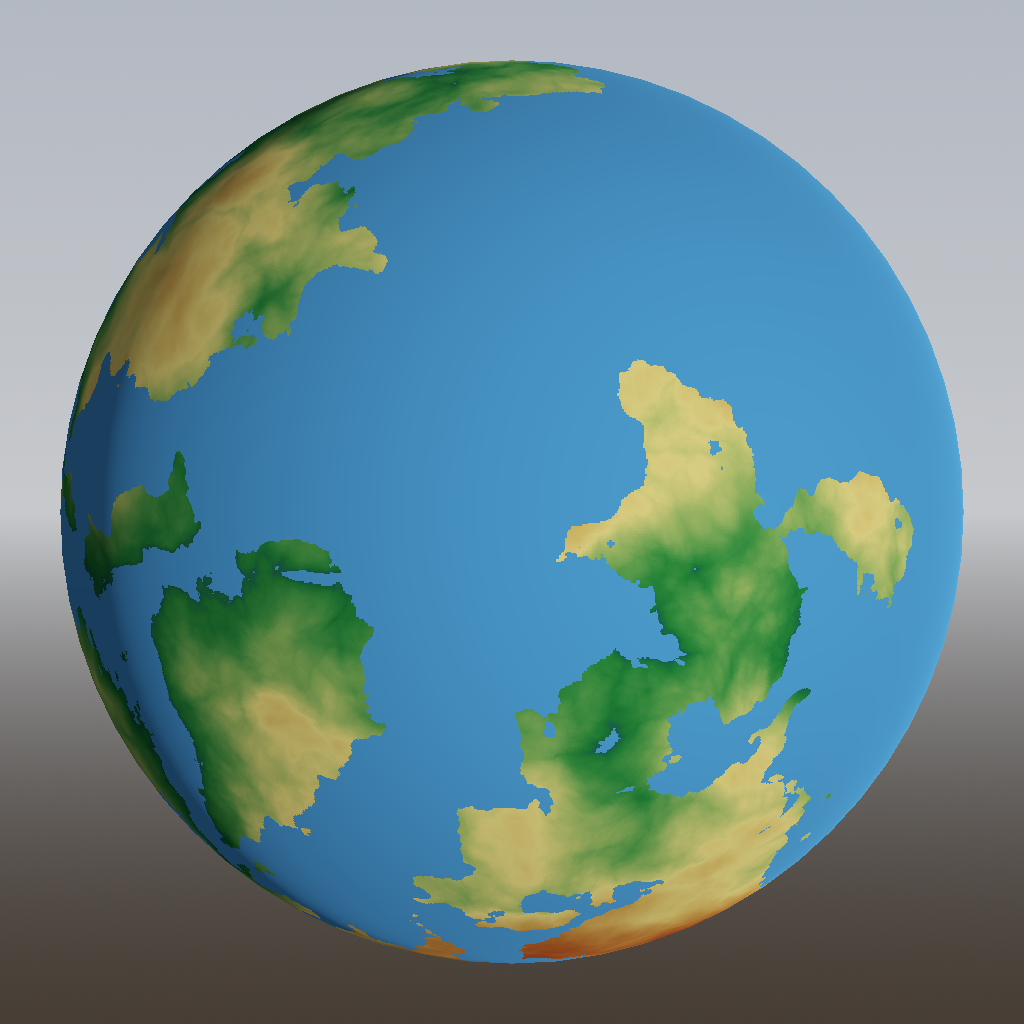

So far, all our land is perfectly flat. Boring! This almost screams for more simplex noise to be added:

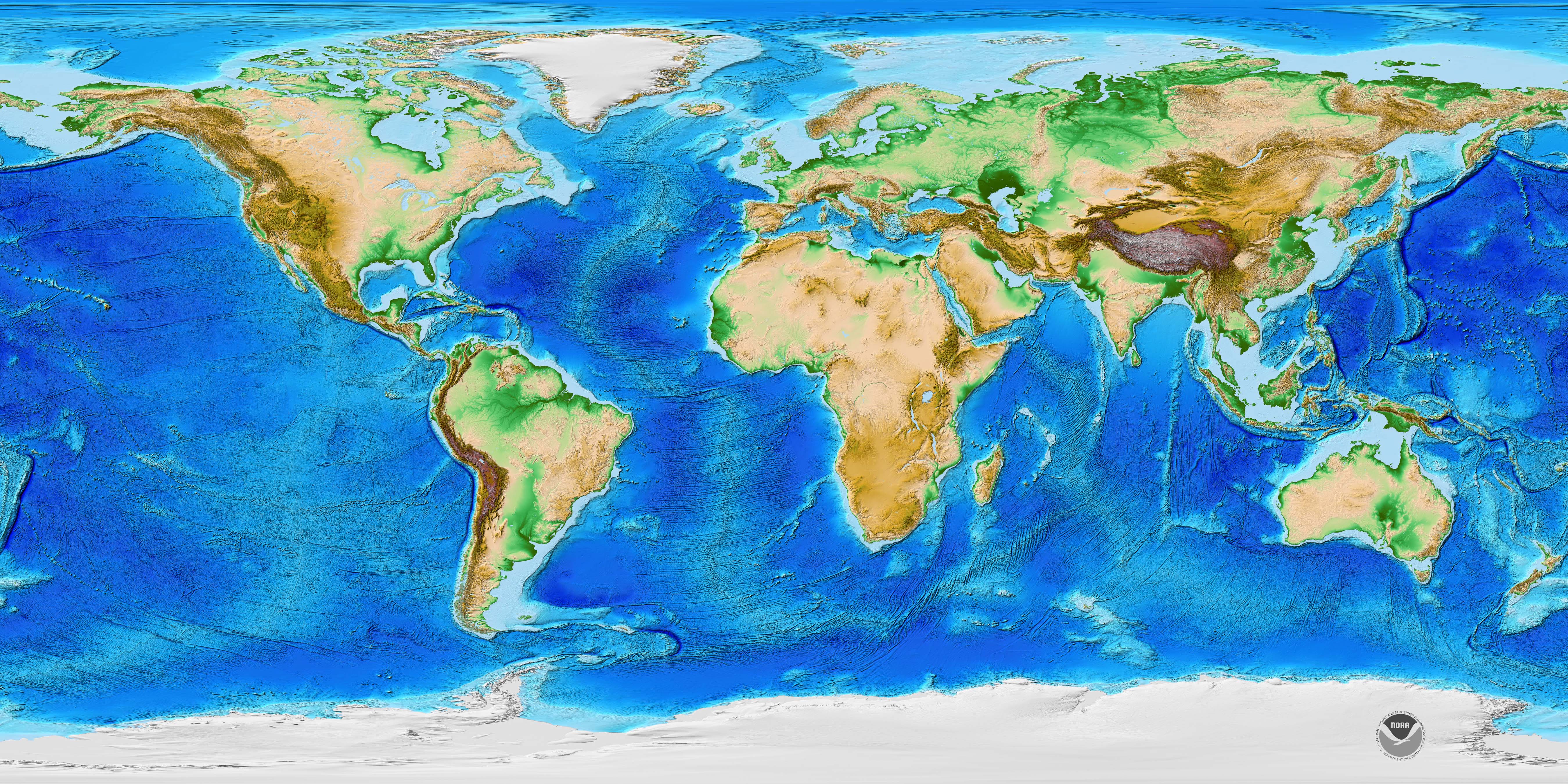

Looking better! Notice that I’m using colour to represent height here, so e.g. yellow doesn’t mean “desert”, it means “about 800 meters above sea level”. The colour ramp resembles the one used in this map from NOAA, so I can easily compare how similar my world is already looking:

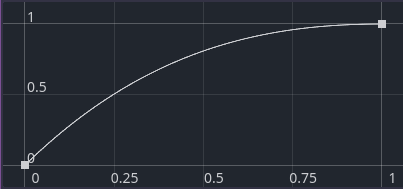

Looking at that height map of the real world, I noticed that heights tend so slope downwards to the coast, rather than ending in 1 km high cliffs like in my generated world. In real life, this is caused by erosion, but that’s another difficult to simulate process that doesn’t offer us much control. So let’s again fake it, by applying a curve:

Every part of the land within some distance from the coast has its height multiplied by this curve:

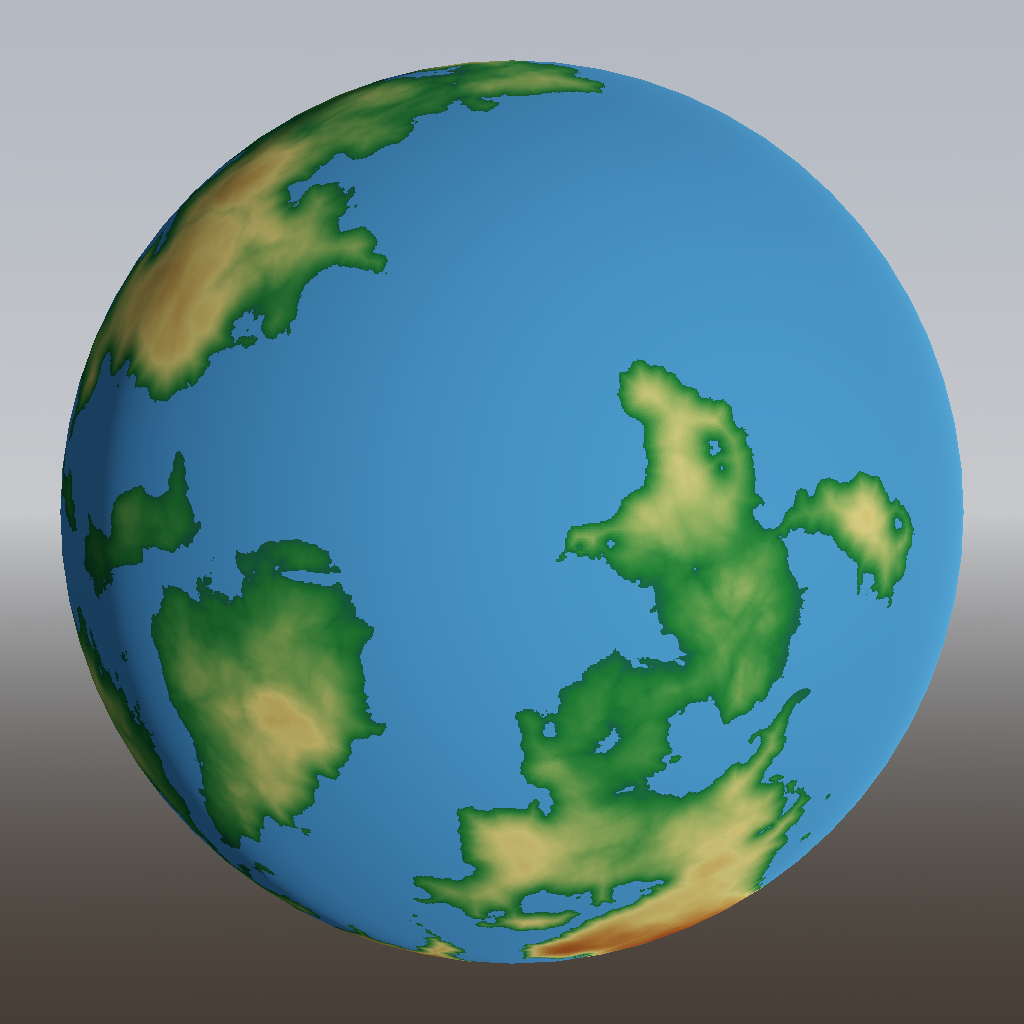

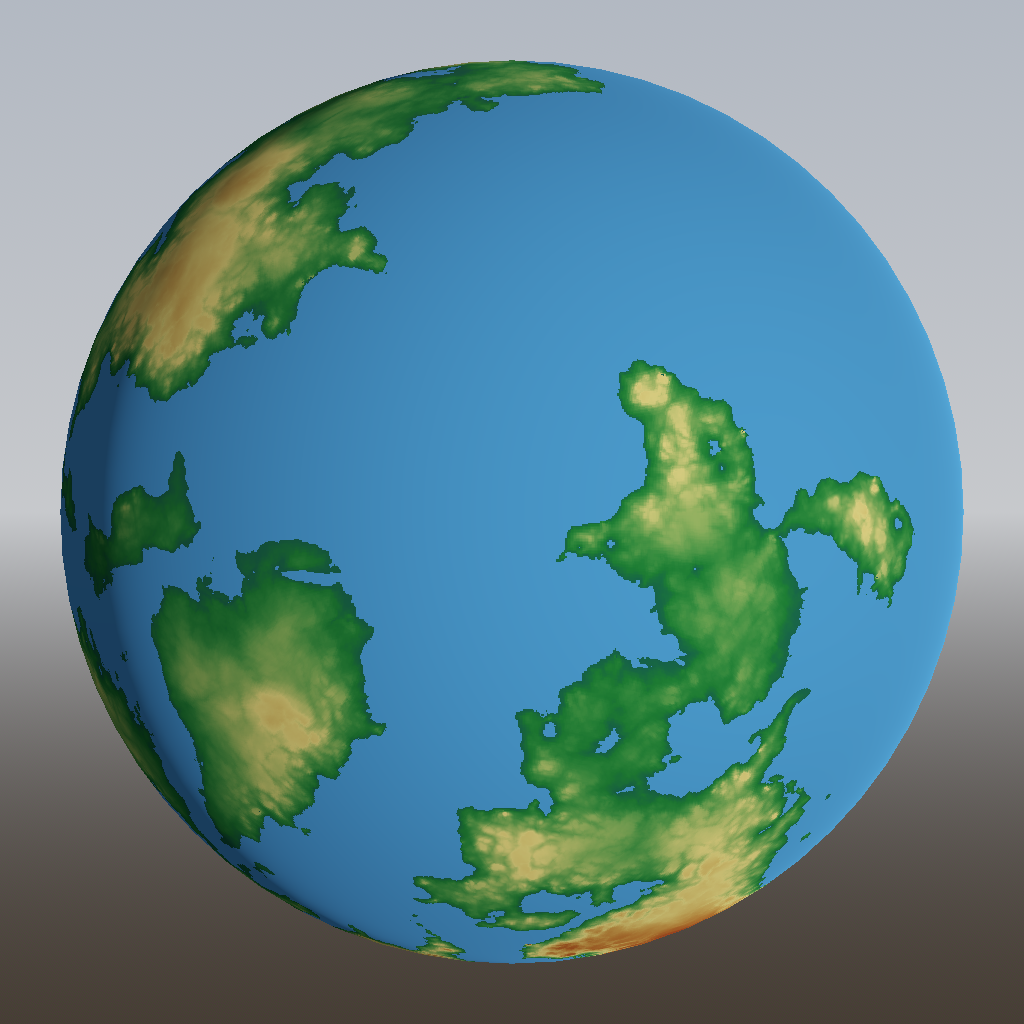

Already better! But it looks a bit bland and uniform. Time for more simplex noise! In this case, I’m using the noise to change the distance over which the curve is applied. A small distance results in a steeper, more cliff-like coast, a large distance in a flatter coast:

We’re off to a good start. In the next post, we’ll tackle tectonic plates and their effects on the geography of our little world.